- Home

- Derek Taylor Kent

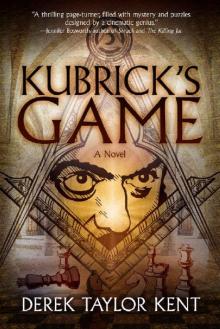

Kubrick's Game Page 2

Kubrick's Game Read online

Page 2

Wilson muttered under his breath, “Slow your roll, man. They get it.”

Mascaro broke out laughing. “Maybe you should teach this class, eh?”

Shawn didn’t understand that Mascaro was joking. “Do you have the authority to offer me the position?”

Wilson slunk down into his seat.

“Young man, I can see that you are a fan of Mr. Kubrick.”

“Stop saying his name wrong! It’s pronounced Kyu-brick. Not Koo-brick. Every time you say Koo-brick it makes my skin crawl.”

Mascaro stepped out from behind the podium. “Perhaps you don’t realize that Kubrick was of Hungarian descent. I have visited Hungary, where everyone pronounces it Koo-brick.”

Without missing a beat, Shawn raised his laptop and read from it. “Kubrick wasn’t from Hungary. He was born and raised in the Bronx. I quote from his IMDB page, ‘According to Stanley’s daughters, the family last name is pronounced Kyu-brick. Not Koo-brick. You see? This is called evidence.”

Shawn closed the laptop and awaited a response.

“Very well, professore,” Mascaro said rolling his eyes, “perhaps you can tell us why Kyu-brick moved the painting and why Kyu-brick edited himself into his movie?”

“Why indeed,” replied Shawn. “That’s what I was hoping we would get to discuss in a film analysis class, but why should we be so lucky?”

Mascaro lowered his head in a mock smile, laughed to himself again, then looked up to the class. “Well, time is up. Mr. Hagan, perhaps we will discuss this subject, and your behavior, further.”

The students avoided Shawn as they exited the theater. With the country’s history of school shootings, students with “mental issues” were not taken lightly. Wilson stuck by his side regardless, and Shawn felt shielded from any insensitive comments.

“Why you gotta go off like that in class?” said Wilson.

“I thought he’d want to know that he was wrong.”

“No, no, no, bro. Look, whenever you feel the need to give a sermon, how about you look to me? If I shake my head, that means it’s quiet time. Okay?”

Shawn wasn’t great at social cues, but he knew when he was being patronized. Still, he appreciated Wilson’s concern for him.

Mascaro, still a little dumfounded, watched Shawn exit the building. “They were right,” he said to himself in Italian. “He is the one I need.”

Within an hour of the “Lolita incident,” word of Shawn’s outburst had spread across campus. Someone had even recorded it, and it gained over 20,000 views on YouTube in its first hour.

Shawn found his favorite table in the back corner of the north campus cafeteria.

Wilson plopped down at the table with a pre-made Chinese chicken salad. “What’s up, wild man?”

Shawn didn’t look up from reading a film review in the Daily Bruin. He had applied to be the newspaper’s film critic that year, but had been turned down because his sample reviews were “too scathing.” The current film review raved about the new G.I. Joe film, causing him to take vicious, tearing bites from his bagel sandwich.

“Hello? Earth to Shawn. Do you read me?”

Shawn lowered the paper and gave Wilson his attention.

“Bad news. Damon dropped out of the race,” said Wilson.

“Explain.”

“He decided to pledge a frat, so he’s out the whole weekend. That means we have a spot to fill.”

The annual Fantastic Race, a citywide scavenger hunt where participants followed a series of clues, puzzles, and riddles around the city, would occur that weekend. Wilson had explained to Shawn that he’d participated the past five years, but never cracked the winner’s circle. This year’s theme was movies, so he thought Shawn’s encyclopedic knowledge would be the key to victory.

“I wish Damon hadn’t dropped out. Sometimes clues can only be solved using teamwork,” said Wilson.

“Should we ask someone from our film class?” said Shawn.

“Who you thinking?”

“On second thought, nobody has really impressed me.”

“Including me?”

“Do you want an honest answer?”

Wilson nodded.

“Including you.”

“What? How have I failed to impress you?”

“Your camera technique is lacking in many areas, the pacing of your editing isn’t crisp, and your lighting is—”

“Okay, I get it.” Wilson shook his head. “Do you always gotta be so brutally honest? You wanna make it in this town? Learn to blow smoke up everyone’s ass.”

“I don’t smoke.”

“It’s an expression! Ah, forget it.”

Shawn could see Wilson was agitated. “To point out your positives, you direct actors effectively. Much better than I could.”

“Thanks, man, that means a lot coming from Honest Abe.”

“Or I could just be blowing smoke.” Shawn giggled to himself.

“Glad you find yourself so funny.”

Shawn squinted at something over Wilson’s shoulder: a laptop screen facing him on the fireplace tabletop. A girl was watching a movie with headphones on, scribbling notes.

Shawn bolted out of his seat.

Wilson called out to him, “Hey! Another lesson! You don’t just get up and leave without warning!”

Shawn zeroed in on his target. He was pleasantly surprised to recognize the watcher as his T.A. from Intro to Filmmaking.

He tapped her on the shoulder. “Sami?”

She paused the video and removed her headphones. “Hello, Shawn. How’s it going?”

When Shawn said earlier that nobody impressed him at film school, he hadn’t been entirely truthful. If there was one person he respected, it was Samira Singh.

She more than held her own with him in debating lenses, Steadicam harnesses, and editing programs. She had shown him tricks he never knew for creating realistic sunlight on a soundstage. She even hooked him up with a job as a camera assistant on several grad-student films.

For a moment he became lost in her bright green eyes and smooth olive skin.

“I um... noticed you were watching my favorite scene from 2001. The four-million year jump-cut from animal bone to space missile blew my mind when I first saw it.”

“Mine too. I’m writing my master’s critique on 2001. You know anything about it?”

So many thoughts rushed through Shawn’s head he had to force himself from erupting into a monologue. Where to even begin? Thousands of obsessed fans had spent years breaking down every frame of 2001, hoping to uncover the hidden meanings. Some contend Kubrick was trying to send us a message through this film that our brains are simply not advanced enough to understand—the audience like those naïve ape-men, marveling at the black monolith, completely unaware of what it represents.

Most interesting to Shawn was how the film was made, rather than why. Why appeared to be anyone’s guess, but knowing how was equivalent to understanding the Egyptians’ construction of the pyramids. Kubrick had to invent modern special effects in order to realistically portray outer space and weightlessness.

Shawn bit his lip and restrained himself from going into all that.

“If you’d like, I can email you some interesting articles I’ve come across.”

“That would be great.”

He paused. The conversation was probably over, but he didn’t want it to end. “Why are you watching this scene?”

“I just noticed that when the bone flies into the air, it starts off spinning clockwise, but after it rises out of frame, it drops back spinning counter-clockwise. Most think it’s an error in editing, but I’m not sure I believe that.”

“You’re right,” said Shawn, bursting into a smile. “It’s not an error.”

“Oh? How do you know?”

“Because it’s not the same camera angle. The background changes. Kubrick turned the camera 180 degrees. Our brain doesn’t even consider that possibility because he’s breaking one of the most common rules of filmmaking.”

/> “The 180-degree line,” said Sami.

“That’s right. In one of the most iconic shots of all time, Kubrick does something that every film student is taught they must never, ever do.”

“Why do you think he did that?”

“I think it’s a setup for the jump-cut to outer space, where direction has no meaning. This jarring misdirection will continue to happen within the spaceships, where astronauts walk on the walls and ceilings. It also foreshadows the final scene in the Jupiter room, when Kubrick systematically breaks one filmmaking rule after another in order to convey the boundless nature of an alien dimension.”

Sami furrowed her brow, considering.

Shawn blurted, “Either that or it was a dumb mistake.”

Sami laughed again.

“I like your theory, but I think it’s symbolic of Kubrick’s main message of the film.”

“Which is?”

“The bone was a tool for violence against their prey and rival ape groups, and in that split second the bone evolves over four million years into a nuclear warhead circling Earth. When it reverses rotation, the message is that in order to take our next major evolutionary step, humans must reverse course and overcome our thirst for violence.”

“You might be right, but your theory is subjective. There’s no way to prove or disprove it.”

“That’s the beauty of art. It emerges from the spirit of its creator, passes through the filter of an observer, and is reborn as something entirely unexpected.”

Shawn was speechless. He’d been analyzing films his whole life trying to unravel the intent of their creators. Should he have been more focused on how films affected him personally?

“Well, thanks for the input,” said Sami. “I should get back to this.”

“Okay,” said Shawn. He turned to leave.

“Wait a second,” said Sami. “What are you doing this weekend?”

“I’m, um, just doing this race thing around the city on Saturday.”

“You mean Fantastic Race? I’ve always wanted to try that. I’m shooting my thesis film project this weekend, but my D.P. had to bail. I remember how good you were from class. The job is yours if you want it. Can’t pay you anything, but you can start building your reel.”

“I would like to very much, but I committed to this race. We had a player bail on us too. We still need to fill his spot.”

“Come on. Isn’t getting a cinematography credit on a grad thesis film more enticing than a silly race?”

“I really, really want to... but I promised.”

“You know what? I like that. Shows you’re not flaky. Tell you what. I’ll join your team and move the shoot to Sunday, but you’re mine all this week for prep. Deal?”

A moment later, Shawn walked back to the table where Wilson was leaning back, arms crossed with a wry smile on his face.

“I can’t believe I’m going to ask this, but... were you macking on our T.A.?”

“Macking?”

“Hitting on her? Spitting game?”

“No. I don’t think I spat any game, but I got us another teammate for Saturday.”

Shawn’s phone vibrated. He pulled it from his pocket and checked his email.

From Professor Mascaro: Meet me in my office as soon as you can. Tell no one where you are going. A matter of utmost urgency. – Antonio Mascaro

At five after four, Shawn entered Mascaro’s closet-sized office. Mascaro had decorated the walls with posters of his most famous films—La Festa Cattiva, Il Ragazzo Scimmio, and Carnevale di Viareggio.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Hagan. Thank you for coming so quickly.”

Shawn eyed the posters.

“Have you seen my films?”

“I’ve seen all of them.”

“Ah? And what do you think?

“They were shot adequately.”

Mascaro chuckled to himself, then looked at Shawn. “About today’s incident... I like your passion, Mr. Hagan. Used wisely it can produce great things, but it must be harnessed. I have received a call from the Dean’s office. They asked if I would like to request a disciplinary investigation into you, but I don’t think that will be necessary. Will it?”

“I would hope not.”

“Good. I tell them there is no need. But another outburst like before, you will not be so lucky.”

Mascaro rose from the chair and sat on the edge of the desk in front of Shawn. “I think you are right that the mistakes in Lolita are not mistakes, but I must take into account the other students of the class. I do not want the films of Kyu-Brick, ha, to intimidate those who have never been exposed. So you see why I choose to do in this way?”

“Yes sir.”

“Molto bene. I am curious. How did you come to know so much about the films of Kubrick? You must be only... eighteen?”

“I’m twenty.”

“You have a young face.”

“I know. Kubrick is my favorite director. When I like something, I study it.”

“So you learn all on your own? No classes?”

“That’s correct.”

“How marvelous! What would you say is the extent of your knowledge?”

“I’ve read every book and article written about him, every interview with his casts, his crewmembers and himself. Not to mention internet analysts and theorists. And, of course, I’ve seen every film multiple times.”

“Multiple? I have a feeling you know exactly how many.”

“None fewer than ten.”

“Well, any grade less than an A-plus will be a grand disappointment for you, yes?”

Shawn replied, “I would be more angered than disappointed by your inaccurate assessment.”

Mascaro laughed and slapped Shawn on his knee.

Shawn couldn’t help but correlate the gesture to the scene in A Clockwork Orange when guidance counselor P.R. Deltoid gets touchy-feely with Alex while trying to ascertain what “nastiness” he was up to the night before.

Moments like this frustrated Shawn more than any other. The lines of social boundaries seemed variable from time to time and person to person. His first instinct was usually to keep his mouth shut and ask his parents later, but now that he was on his own, it was difficult to make these decisions for himself.

Mascaro continued. “I was only joking! I want you to feel comfortable with me.” He reached over and squeezed Shawn’s bony shoulder. “Think of me as a colleague, not your professor.”

Shawn stiffened. “What for?”

“You must be wondering why I told you not to tell anybody that you were coming here. You heeded my request, yes?”

“I didn’t tell anyone,” Shawn answered.

Mascaro leaned in. “I want to show you something that nobody else can know about. Can I trust you?”

Mascaro placed his hand on Shawn’s other shoulder, but Shawn turned swiftly and swatted it away.

Mascaro jumped back in surprise.

“Don’t touch me again.”

“My boy, this is a gesture of friendship. There is no other meaning. But I respect your wishes, of course.” Mascaro circled back around his desk and sat in his chair. “Have a look here. This is what I want to show you.”

He opened the top drawer of his desk and pulled out a large black envelope. The address seemed to have been painted in white with a fine brush. It was addressed to:

The UCLA Film School and Archive

c/o A Worthy Opponent

“Go ahead,” said Mascaro. “Open it.”

Shawn pulled out a black-and-white photograph the size of a sheet of paper. Shawn recognized the image immediately.

This was the famous Look Magazine photograph published after the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The sadness of the newsstand vendor, who might normally be upbeat at the sales potential of such a momentous event, encapsulated the melancholy of the entire nation in one stunning image. The photographer was sixteen-year-old Stanley Kubrick.

The photo landed teenage Stanley a job as a photo

grapher, which would hone his eye and mold his expertise in camera operation.

“You are familiar with the photo?” inquired Mascaro.

“Very,” replied Shawn. Something about the photo seemed off to him, but he couldn’t tell what. “Who sent it?”

Mascaro took out a shipping label and placed it on the desk. “The sender was Stanley Kubrick, from a post office box in England.”

Shawn raised an eyebrow. “You are aware Kubrick has been dead for over fifteen years?”

“It was likely sent on his behalf. Or, perhaps he arranged for the package to be sent before he passed away. I checked the postal mark, and it originated from the post office nearest the Kubrick estate in Hertfordshire, England.”

“Why was it sent?”

“At first, I thought it was meant for the upcoming museum exhibit on Kubrick opening at LACMA.”

Shawn nodded. He had bought the first available tickets to the Stanley Kubrick exhibit for its grand opening that Tuesday at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Rumor had it they would display countless props, memorabilia, plus research notes and working scripts—a true look inside the mind of a genius.

“At first, I believed this was meant for the exhibit,” Mascaro clarified. “But then, I examined the back of the photo.”

Shawn turned the photograph over. On the back was a phrase written in what Shawn recognized as Kubrick’s barely legible handwriting. It read:

Follow me to Q’s identity.

“What does this mean?” Shawn didn’t look up.

Mascaro leaned over and slapped the desk, grabbing Shawn’s attention. “That, Mr. Hagan, is what I am hoping you will be able to tell me.”

That evening Shawn took the bus over to Wilson’s apartment in the Wilshire Corridor. While most UCLA students lived within walking distance of campus, Wilson lived two miles away amongst the L.A. elite.

On the way, he examined a copy of the photo Mascaro had made for him. He had a few ideas of what Follow me to Q’s identity might mean, but he didn’t want to reveal anything too soon. He had an appointment with Mascaro the following Monday to discuss the photo further.

Wilson’s place could be the definition of a pimp pad. Unlike Shawn’s tiny dorm room that he shared with a microbiology major who rarely left the research lab, Wilson’s spacious, modern apartment offered a view all the way to the ocean. The interior was no less impressive: shining hardwood floors, suede white sofa, and 60-inch flat screen with Bose surround sound. Shawn marveled at a poster of Raiders of the Lost Ark signed by Steven Spielberg and an original Star Wars poster signed by George Lucas, both purchased off eBay courtesy of Wilson’s residuals.

Kubrick's Game

Kubrick's Game